Operator Note: Competition is a Privilege

It means you’re in a space that matters — one that’s real enough for others to chase and hard enough to stay in.

Hi, I’m Shan, and I run Xandro Lab — a science-first longevity brand based in Singapore. Every Sunday, I sit down here on Out of Singapore to write about what’s really happening — not the polished parts, but the process of building something in real time.

This week’s note is about competition. Not the kind they teach you in business school — think SWOT analysis, BCG Matrix, or Porter’s Five Forces — but the kind you feel when a new brand shows up on your feed, prices its product 50% lower, and starts outselling you. The kind that makes you question your pricing, your speed, and your strategy. I’ve realized over time that I don’t just tolerate competition. I love it. It’s the most honest signal in business — a mirror that tells you where you actually stand.

Because every industry report lies. The $500-billion market reports. The consultant projections. Even the Google Trends charts everyone screenshots to show growth. None of that reflects your reality. It doesn’t tell you how many people are actually buying, or how quickly they’re switching, or whether they’ll buy from you again next month. Competition, on the other hand, is real-time data. It’s the purest signal that something is working — either for you or against you. It’s also the only metric that can’t be faked. You can buy ads, pump vanity metrics, raise rounds, or spin PR stories, but you can’t fake what happens when another player enters your space and the numbers move.

That’s why I don’t see competition as a threat. It’s a pulse — a living, moving feedback loop that tells you what consumers are actually paying attention to, and what they’ve stopped caring about.

Today’s Reading

What competition really tells you

The reality of being undercut

What competition reveals about your goals

The Singapore problem — easy markets, fast imitators

How I benchmark competition

Framework for response — cost, innovation, community, distribution

The race you choose to run

Let’s start.

1. What competition really tells you

The presence of competition means one thing — the market is alive. It’s not a theory anymore. There’s demand, awareness, willingness to pay, and a cultural shift already underway. If you’re building something new, competition is validation. The absence of competition, in most cases, means there’s no market yet — or worse, that there was one and it died.

So, I’ve stopped seeing new entrants as threats. When a brand launches in our category, it’s proof that we were right — that there’s momentum, that people are talking, that we helped open a door others now want to walk through. For an operator, that’s gold. Competition becomes a form of market research, delivered in real time. It tells me if my positioning still holds, if our story still resonates, if our pricing or packaging has started to look tired. You don’t need a McKinsey report to tell you that. Just watch what happens when someone launches a similar product — do you lose sales or gain conviction?

And in some ways, competition exposes your blind spots faster than any internal review ever could. It tells you what you’ve stopped noticing about your own brand. It reminds you that momentum is fragile — that while you’re refining, someone else is releasing. That while you’re planning your next big launch, someone’s already running their tenth ad on the same idea you thought was unique. For me, that’s not discouraging. It’s fuel. It’s data, pressure, and perspective — all rolled into one.

2. The Reality of Being Undercut

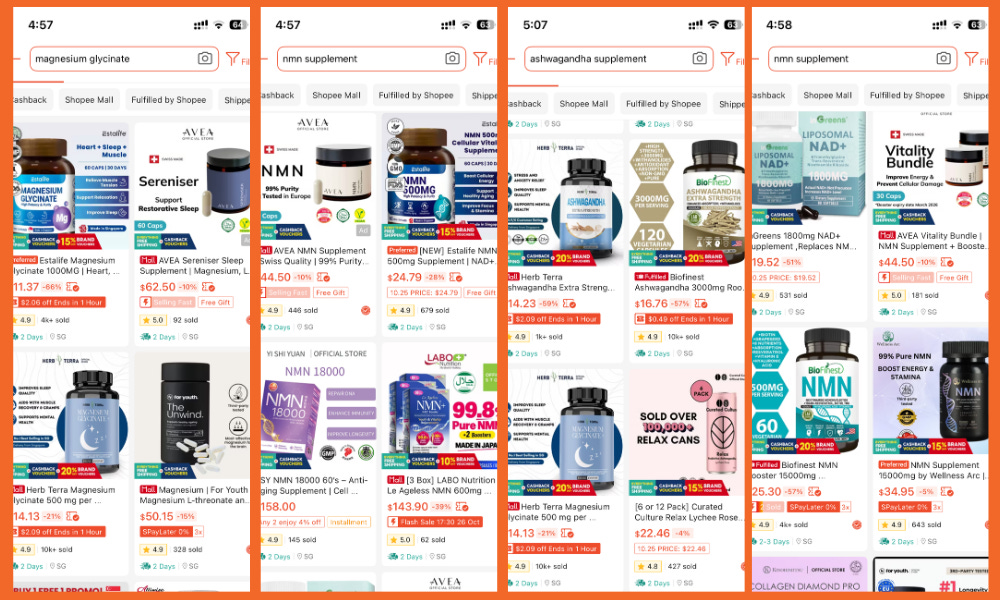

The hardest part about competition isn’t that someone copies you — it’s when they copy you and still sell better. Over the last year, we’ve seen this play out repeatedly. Our two key products, NMN and Magnesium Glycinate, both started facing new entrants almost every quarter. With NMN, the Japanese brands moved first. The formula was almost identical (albeit with tons of fillers & binders), but they carried that “Made in Japan” credibility and priced at $50 a bottle while we sold at $80 for 30,000 milligrams. Within weeks, they took the market by storm. We didn’t crash, but we didn’t grow either. That’s worse in some ways — when you’re still standing, but your graph has flattened.

Then came Herbterra and EstaLife on the magnesium front (now they are competing on NMN as well). They priced between $12 and $15 while we stayed at $18 to $20 per bottle. That’s when the real challenge began — the slow erosion of pricing power. You can’t make a clean magnesium glycinate for $12 unless you’re cutting corners somewhere. I know the cost structure by heart: finished goods alone are $5 to $8, add shipment, logistics, and marketing, and there’s barely any room left for quality. But markets don’t reward purity; they reward perception. And perception, for a while, belongs to whoever was cheaper.

The first instinct as an operator is to fight back — match price, push volume, drive offers. We’ve done that too, a little. But every time you do, you feel something shift internally. You start thinking like a trader instead of a builder. You start making short-term calls that hurt the long game. Still, it’s not easy to watch your product — one you’ve built, tested, and stood behind — get outsold by someone who came in three months ago. It’s humbling. It’s also strangely useful. It forces you to zoom out.

When a new player undercuts you, it’s not just about cost — it’s about what you’ve stopped noticing. Maybe your message has gone stale. Maybe your creative looks tired. Maybe your community hasn’t heard from you in a while. Competition makes you look in the mirror, brutally and immediately. It’s a wake-up call, not a death sentence.

Extra Note: I don’t blame people for switching. Supplements are expensive, and most consumers are just trying to find something that works. When you can’t see or feel results immediately, it’s easy to assume another brand might do better. That’s fair. The onus is on us — the makers — to prove consistency, safety, and transparency. If we don’t, people should move on.

3. What Competition Reveals About Your Goals

How you see competition depends entirely on what you’re trying to build. If your goal is to be the biggest supplement brand in Singapore — say, doing 2-5 million dollars a month — you can absolutely get there by running a tight, efficient, profitable business. You focus on pricing, logistics, local retail expansion, and keep reinvesting in acquisition. That’s a strong, sustainable business and it’ll probably last a decade. There’s nothing wrong with that path. But it’s not mine.

I’ve always looked at Xandro Lab as something more global — not just a supplements company, but a longevity solutions company built out of Singapore. Which means the way we evaluate competition has to shift too. I’m not just competing on price. I’m competing on credibility, perception, reputation, partnerships, science, PR — things that compound across markets. The quality of your network, the kind of people who associate with you, the depth of your science — all of that matters when you’re trying to build something with global relevance. Price becomes a factor, but not the differentiator.

That’s why we’ve chosen a harder route — investing in research, clinical studies, brand storytelling, community, and education. None of this is needed to run a successful local supplements brand (not entirely I mean). But it’s necessary to build trust at a level where people in different countries, cultures, and age groups see you as the standard for longevity science. That’s the game we’re playing.

Competition, in that sense, acts as a compass. It reminds you to check if the game you’re playing is still aligned with your long-term goal. Because sometimes, what feels like losing is just not competing in the same race.

4. The Singapore Problem — Easy Markets, Fast Imitators

Singapore is one of the easiest and hardest markets at the same time. Easy, because consumers here are incredibly open to trying new things. Hard, because that same openness means loyalty is fragile. You can drop your price by ten dollars and instantly find ten thousand new buyers. People don’t need a deep reason to switch — they just need a nudge. It’s not about distrust; it’s about curiosity. Consumers here like to experiment, and that creates a constant churn that most founders underestimate.

That’s why I often say Singapore is a great launchpad, not a moat. It’s an amazing place to test ideas, see what resonates, and build early traction. But it’s not built for complacency. The same things that make this market efficient — high awareness, strong logistics, digital adoption — also make it brutally fast in how new brands emerge and old ones fade. You can build credibility for two years and lose share in two weeks. That’s not exaggeration. I’ve seen it happen, not just to us but across every category — beauty, wellness, functional food. The barrier to entry is low, the cost of experimentation is low, and the consumer’s willingness to switch is high.

It’s also why I’m not shocked anymore when a new brand succeeds without any real background or credibility. The acceptance rate here is wild. You don’t need to be GMP-certified or clinically tested or even manufactured locally. As long as your branding looks good and your price feels right, you’ll get sales. And that’s not cynicism — it’s just how consumer psychology works in a dense, high-income, low-commitment market. People buy fast, try fast, and move on fast.

This environment teaches you two things as an operator. One, you can’t rely on just one product — especially not in Singapore. Unless you have deep pockets or a single hero product that can survive for years like AG1, you need assortment. You need to keep launching, testing, and learning. And two, you can’t take early success too seriously. Singapore will show you traction long before you’ve built real depth. That’s both the opportunity and the trap.

Extra Note: In markets like the US, UK, or Australia, competition looks very different. The US is crowded but fast-moving — everyone’s fighting for attention, and differentiation comes from science or storytelling, not price. The UK is slower and more credibility-driven; consumers want proof and stick around once they trust you. Australia sits in the middle — highly regulated, dominated by legacy players, and tough to disrupt without retail presence. Singapore, in contrast, moves fast. It rewards experimentation, not endurance — which makes it a great launchpad, but a tough place to build lasting advantage. Unlike US, UK and AU, it’s also not a huge market.

5. How I Benchmark Competition

I’ve learned that benchmarking competition isn’t about obsessing over who’s cheaper or louder — it’s about understanding why they’re moving faster or slower than you. I start with the basics: how similar is the product, what form it’s in, how it’s priced per gram, and how many units it’s actually selling. It’s surprisingly easy to check. Platforms like Shopee and TikTok tell you a lot — order counts, review numbers, engagement trends. Even without direct data, you can sense how fast something is moving by how often it’s showing up on people’s feeds.

Then there’s the on-ground feedback — the part you can’t Google. When you talk to your own consumers often enough, you start to see patterns. People rarely buy only from you. They’ll tell you what else they’ve tried, why they switched, what they liked, and what they didn’t. That’s the real intel — it’s unbiased, straight from the wallet. You also learn a lot from the supply chain. Because we work directly with manufacturers, we can see where raw material prices are trending, which tells you where the market’s headed. NMN, for instance, has halved in cost over the last two years. Magnesium glycinate is now at rock bottom. That’s not a good thing — it means the market is flooded, quality is falling, and buffered variants are everywhere. We’ve even had to strengthen our own QC because some batches started showing inconsistencies.

So benchmarking, for me, is less about comparison and more about pattern recognition. It’s connecting signals — price drops, review spikes, new players entering, or old ones quietly disappearing. Each of those is a datapoint. When read together, they tell you the real story of where your category is going.

6. Framework for Response — Cost, Innovation, Community, Distribution

You can’t fight every battle. So when competition shows up, the first question I ask isn’t “how do we beat them?” but “where are we even fighting?” Because there are only four levers you can really pull — cost, innovation, community, and distribution. Everything else is noise.

Fighting on cost is the easiest, and also the fastest way to die. It works if you’re playing the commodity game — if you can sell a million bottles a year. At that scale, you can afford to lower price and still win on absolute profit. But if you’re only moving ten thousand units, cheaper pricing doesn’t change your business, it just erodes your margins. I’ve learned that lesson the hard way. You can’t pay salaries with percentage margins — you need real cash flow. So when the market goes into a price war, I usually step aside. That’s not our race.

Innovation is where we can win, and that’s where we’re putting our weight. Most single-ingredient products eventually become commodities — magnesium, NMN, vitamin D, all of them. Anyone with 50 thousand dollars can launch one. The defensibility comes from what you build next — proprietary formulas, unique delivery systems, and products that solve real use cases like sleep, recovery, or cognitive health. That’s where the premium sits, and that’s where we’re heading with Protocol X and our upcoming blends.

The third lever is community. You can’t outspend everyone, but you can outbuild trust. Most people underestimate how much a strong community shields you from price pressure. If people believe in your intent — that you’re genuinely building for longevity, not just selling capsules — they stay. That’s why we keep doing events, partnerships, and educational sessions even though they don’t directly show ROI. They build something harder to measure — trust velocity.

And finally, distribution. This is our weakest link today, and it’s what I need to fix over the next twelve months. You can have great products and strong community, but if you’re not available where consumers shop — pharmacies, retail, new markets — you’re capping your own growth. That’s the next muscle we’re building, both locally and globally. Because in the long run, competition doesn’t just test your pricing; it tests how complete your ecosystem is.

Extra Note: The next phase of competition won’t be about ingredients — it’ll be about systems. Brands will move from selling supplements to designing protocols: figuring out what each person actually needs. You can already see it with Bioniq in the UK or Whoop Labs, where blood tests and lifestyle data guide supplement plans. As ingredients become commoditized, the real advantage will come from personalization — helping people correct deficiencies instead of just buying bottles. Because food today gives us enough calories but not enough nutrients, the brands that design smarter intake systems, not just smarter capsules, will win the next decade.

7. The Race You Choose to Run

At some point, you realize competition isn’t the enemy — confusion is. The noise, the temptation to react to everything, the panic of seeing someone else move faster or cheaper. That’s what really hurts. Because once you start reacting to every move in the market, you stop leading. You stop playing your game.

Over time, I’ve learned that every brand has to decide which race it’s really in. Some are in the volume race — they move volume, make quick cash, and keep launching faster than anyone else. Others play the perception race — they win on image, packaging, and hype. And then there are those in the patience race — the ones building with science, consistency, and long-term credibility. That’s the one we’ve chosen, even if it means slower growth and fewer viral moments. (ofcourse, I am tempted to play both volume race and perception race).

You don’t get to choose your competition, but you do get to choose your response. And that response slowly defines who you become — not just as a brand, but as an operator. Every decision you make under pressure leaves a fingerprint on the company’s DNA. Over time, that becomes identity. You can say you’re science-first or performance-first, but the market will believe it only if your actions prove it — in how you price, how you react, and how you hold your ground when others cut corners.

Competition, in that sense, isn’t there to destroy you. It’s there to clarify you. It exposes what you actually believe in, what you’re willing to defend, and what you’re willing to let go. And maybe that’s why I love it — because it doesn’t just make you sharper; it makes you honest.

Closing thoughts

The longer I’ve been building, the more I’ve realized that competition is a privilege. It means you’re in a space that matters. It means you’ve created something people think is worth chasing. And it means you now have to decide what kind of player you want to be — not just for the next quarter, but for the next decade.

I don’t wake up thinking about how to beat anyone. I wake up thinking about how not to dilute what we’re building. Because if you keep building with integrity, consistency, and clarity, the competition eventually organizes itself around you. That’s the quiet part no one talks about — that real advantage doesn’t come from being louder or cheaper; it comes from being sure.

Competition will always be there — new names, new prices, new trends — but the question never changes: what game are you really playing?

See you next Sunday,

Shan