Biggest Health Hack of the Decade

Over the last four years, one simple habit quietly improved my health, focus, and daily clarity. It didn’t add complexity. It removed it.

Hi, I’m Shan. I run Xandro Lab, a science-first longevity brand based in Singapore.

Every Sunday, I write about what we are building, what I am learning, and how the journey feels from the inside as someone operating at the intersection of health, performance, recovery, and business. Most of these notes come from the backend of the business. From decisions that don’t look clean on slides. From moments of doubt. From things that work quietly and things that break loudly.

Health shows up often in these notes because building a longevity brand forces you to look very closely at your own life. You can’t talk about resilience, performance, and long-term health without eventually asking uncomfortable questions about how you live day to day.

Over the last few years, helping more than 30,000 people improve their health has slowly turned into a personal mission. Not in a dramatic way. More in a quiet, consistent way. I want to reach a million people eventually. With habits that actually survive real life.

I’ve been quiet for the last two weeks.

That wasn’t intentional. The past couple of weeks were packed with two of the biggest events of the year for us. HYROX and Singapore Marathon, where we ran our biggest booth yet and met hundreds of people face to face. It was also the first time we seriously tried selling products offline. It wasn’t perfect, but it taught us a lot.

Inventory was tight, so we could only sell so much. But the learning was valuable. Seeing people try products in real life, ask questions, hesitate, come back, and eventually decide was eye opening. Some customers switched from other brands, others knew from existing channels, again some new about the ingredients and were glad it was Singapore made. I also met fair share of sceptics and non-believers. Talking to them and understanding their perspective was gold to me.

Today’s reading

The change I made in 2021

Why skipping breakfast looks harmful in science

Skipping breakfast vs intermittent fasting, and why context and nutrition matter

Men vs women, and why fasting has to be phase-based

Let’s start.

1. The change I made in 2021

In early 2021, I made a very simple change.

I stopped eating breakfast.

At the time, it had nothing to do with longevity or metabolic health or mental clarity. I wasn’t thinking in those terms at all. I was just trying to lose some weight. There was a 30-day challenge running in the office, and one of my colleagues casually suggested that I try removing breakfast from my daily meals.

That was it. Just a suggestion that sounded slightly uncomfortable but doable.

When I first stopped eating in the morning, it felt wrong. Almost like I was doing the opposite of what I had been taught for the last 30 years. Breakfast was supposed to be important. Essential, even. Something you don’t skip unless you’re careless or irresponsible.

My parents were worried. People around me kept asking if I was okay, if I was trying something extreme, if I was harming myself.

The first six months were uncomfortable.

My stomach would growl. Loudly. In meetings. In the office. Around people. I felt embarrassed, distracted, and oddly ashamed, like I was cutting corners in life or being unnecessarily harsh on myself.

Mentally, it was harder than the hunger itself. Like the day hadn’t properly started because I hadn’t eaten. Walking around with an unresolved task in the back of my mind.

At some point during this phase, I came across an explanation that shifted how I thought about it. During fasting, the gut goes through its own cleaning and motility cycles. That growling sound wasn’t hunger in the dramatic sense I imagined. It was the digestive system doing maintenance work between meals. The intestine essentially cleaning itself. And if you’re constantly eating, this process doesn’t really get a chance to happen.

That didn’t suddenly make it pleasant. But it made it less alarming.

Almost without realising it, about six months later, breakfast had disappeared. Eating two meals a day became normal. Not something I thought about. Not something I planned around. Just normal.

And somewhere along the way, something unexpected happened - My days started to feel lighter. I would wake up. Train. Have my coffee. Go to work. And I wouldn’t think about food.

Around noon, I’d eat lunch. Sometimes I’d snack if stress was high. I’d have dinner around seven or seven-thirty. No food before bed. No constant planning around meals. No mental negotiation about what to eat next.

I didn’t have to decide what to eat three or four times a day. I didn’t have to cook in the morning, order food, or think about where my next meal would come from. A whole category of small decisions simply disappeared.

Over time, the results showed up without effort.

In early 2021, my weight hovered around 80 kg. For almost four years now, it has stayed between 64 and 66 kg. Even during phases where I’m not running much or lifting regularly, my weight stays stable. I don’t manage it consciously. I don’t think about it much at all.

My blood work has been consistently good. No major vitamin or mineral deficiencies, apart from vitamin D, which has nothing to do with food timing. Fat levels are normal. Muscle mass has improved steadily as I’ve trained more.

Mentally, I feel sharper. Not wired. Not euphoric. Just clear.

The only times I eat it now are when I’m travelling and staying at a good hotel, or when I’m home with my parents. Even then, it’s usually late. More of an experience than a routine.

This is what the habit really is. Time-restricted eating or Intermittent Fasting. Creating a longer window where your body isn’t constantly digesting. Nothing more dramatic than that.

And for me, quietly, over time, that made a bigger difference than I expected.

2. Science is against skipping breakfast. Why?

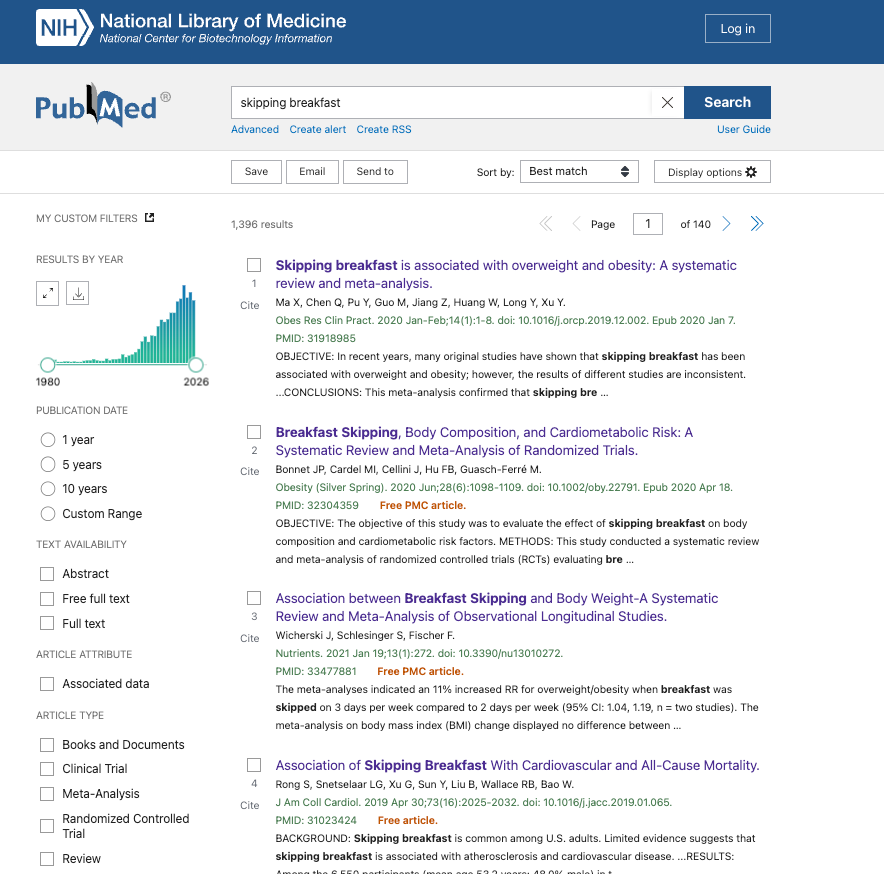

If you search PubMed for “skipping breakfast,” the results feel almost moralistic.

Skipping breakfast is associated with higher risk of diabetes. Higher cardiovascular mortality. Poorer mood. Lower vigor. Higher anxiety. Worse metabolic outcomes.

On paper, the case looks settled. Breakfast matters. Skipping it is harmful. So why does this clash so sharply with the lived experience of so many people, including mine?

The answer sits in an uncomfortable place where epidemiology, behaviour, and physiology get tangled, and where skipping breakfast is often studied as a proxy for disorder, not as a deliberate metabolic strategy.

Let’s unpack this carefully.

Most “anti-breakfast” science is observational, not interventional

A large share of the evidence against skipping breakfast comes from observational cohort studies, not controlled experiments.

For example, “large meta-analyses have reported that people who skip breakfast have higher risk of type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease compared to those who eat breakfast regularly. One such analysis covering nearly 100,000 participants found a roughly 30–50% higher relative risk of diabetes among habitual breakfast skippers, even after adjusting for BMI”

On the surface, that sounds damning. But observational studies answer a very specific question:

“What kind of people tend to skip breakfast?”

Not:

“What happens if a healthy adult intentionally practices time-restricted eating?”

And those are very different questions.

When you look closely, habitual breakfast skippers in these cohorts are more likely to:

Sleep poorly

Smoke

Eat irregularly

Consume more ultra-processed food later in the day

Have lower socioeconomic stability

Exercise less consistently

Skipping breakfast here is not the intervention. It’s a signal of a chaotic lifestyle.

In epidemiology, this is called residual confounding. You can statistically adjust for BMI, smoking, or income, but you cannot fully adjust for patterns like stress, sleep debt, or disordered eating rhythms.

So when the conclusion reads “skipping breakfast increases disease risk,” what it often really means is: “People with unstable routines tend to do worse over time.”

“Breakfast is the most important meal” is not a scientific conclusion

The idea that breakfast is the most important meal of the day is deeply cultural. It emerged from agricultural labour patterns, early industrial workdays, and later, cereal marketing.

When researchers have tried to test this claim directly, the results are surprisingly underwhelming.

Controlled trials from the Bath Breakfast Project and others show that, in both lean and obese adults, regularly eating or skipping breakfast does not reliably change body weight, metabolic rate, or total daily energy expenditure when calories are controlled.

What does change is behaviour.

People who eat breakfast often compensate by being slightly less active later. People who skip breakfast sometimes compensate by eating more later. The body adjusts.

Which brings us to an important point that rarely makes headlines: Skipping breakfast does not automatically create a metabolic advantage. And that is exactly why many breakfast studies fail to show benefits.

3. Skipping breakfast vs intermittent fasting are not the same thing

This is where most of the confusion lives. In many studies, “skipping breakfast” simply means: Eating late at night, sleeping poorly, delaying the first meal randomly, snacking inconsistently.

Intermittent fasting, by contrast, is defined by:

A consistent eating window

A prolonged fasting window

Zero or near-zero calories during the fast

Alignment with circadian rhythms

Time-restricted eating, the form I practice, is a structured intervention. When researchers study intermittent fasting directly, the picture changes.

Controlled trials and mechanistic reviews show that intermittent fasting can:

Improve insulin sensitivity even without weight loss

Reduce inflammatory markers

Increase metabolic flexibility

Improve gut microbiota diversity

Lower fasting glucose and blood pressure

These effects are seen precisely because the body is not constantly digesting.

Fasting creates metabolic transitions. Breakfast skipping (with bad lifestyle practices that impact sleep & recovery), as studied in population surveys, usually does not.

Nutrition matters

One thing I should be very clear about, because it’s often misunderstood, is that fasting only works when nutrition is complete. Skipping breakfast or compressing eating windows does not mean eating less of what your body actually needs. Protein still matters. Carbohydrates still matter. Fats still matter.

The goal is not deprivation, it’s timing. On days where training volume is higher, stress is higher, or recovery feels off, eating earlier or eating more is not a failure. It’s adaptation.

4. Men, women, and gender considerations

Men and women do not respond identically to fasting.

Hormonal environments are different. Stress responses are different. Energy availability signals are processed differently. Anecdotally and clinically, many women report that fasting feels harder, especially when layered on top of poor sleep, high training volume, or chronic stress. Irritability, fatigue, cycle disruption, and anxiety are not uncommon when fasting is applied too aggressively or without adequate nutrition.

At the same time, intermittent fasting has shown benefits in specific female populations, particularly women with insulin resistance or PCOS, where improvements in metabolic and hormonal markers have been observed. The difference, again, is context. Lean versus insulin-resistant. Sedentary versus highly active. Well-rested versus chronically stressed.

This is where I think fasting is often misunderstood. It doesn’t have to be static.

Fasting does not need to be an everyday, forever rule. It can be phase-based. There are phases of life where longer fasting windows feel effortless and supportive, and phases where they feel draining. Training blocks, work stress, travel, sleep debt, illness, even emotional load all change how much fasting the body can tolerate.

Some weeks, fasting simplifies life. Other weeks, eating earlier is the more intelligent choice.

Longevity is not just about discipline. It’s about adaptability. The right eating pattern is the one that supports sleep, mood, work, training, and recovery at the same time. If fasting enhances that balance, it’s useful. If it erodes it, it’s the wrong tool, regardless of how popular it is.

For me, the habit survived because it reduced stress rather than adding to it. That is the litmus test I would use for anyone considering it.

Closing notes

The biggest takeaway for me, after four years of living this way, is not that skipping breakfast is superior. It’s that removing unnecessary friction compounds in ways you don’t notice day to day, but feel very clearly years later.

This habit worked for me because it simplified something fundamental. It reduced decisions. It reduced noise. It gave my body longer stretches of rest from constant digestion, and it gave my mind longer stretches of uninterrupted focus. It survived work stress, travel, family life, and changing training loads. And anything that survives real life for that long is worth paying attention to.

That doesn’t make it universal. It just makes it useful.

Before I end, I want to zoom out for a moment.

If you’re one of our consumers, I owe you an apology. The last month and a half has been difficult operationally. We hit a new revenue milestone, but we failed on execution. Some orders took far longer than they should have. Production and inventory cycles became our biggest bottleneck, and we felt the consequences of running too close to the edge.

November was especially hard. We dropped prices too aggressively, took more orders than we could fulfil, and made very little margin doing it. On paper, it looked like growth. In reality, it strained cash, operations, and trust all at once. That’s a tough combination.

We also spent on marketing heavily. Out-of-home ads, MRT placements, marketplace platform spend, events like HYROX and the Singapore Marathon. We learned a lot, especially from selling and speaking to people face to face. But the costs were real, and the timing wasn’t forgiving.

Right now, the focus is simple. Stabilise. Fix inventory cycles. Improve delivery timelines. Get back to healthy margins. Serve existing customers well before chasing new ones. Make structural changes to production and team capacity so the system doesn’t crack every time we push it.

Personally, this has been a stressful period. I’m not pretending otherwise. When multiple problems show up at the same time, the only way through is to solve one thing at a time and not panic. I know this won’t be the last hard phase. There will be many more. But getting through this one matters.

And maybe that’s where this essay quietly connects back to the habit I wrote about.

The things that last are usually not dramatic. They are the boring decisions that reduce load, conserve energy, and give you enough room to deal with what comes next. In health. In work. In life.

I’m back to writing now. Back to routine. Back to thinking clearly on paper.

Until next Sunday.

Shan